Knowledge

A Review of Research on Ceramic Shell for Investment Casting

I'd like to share with you the technical literature "An overview of ceramic molds for investment casting of nickel superalloys", which is probably the most comprehensive review on ceramic shell research at present.

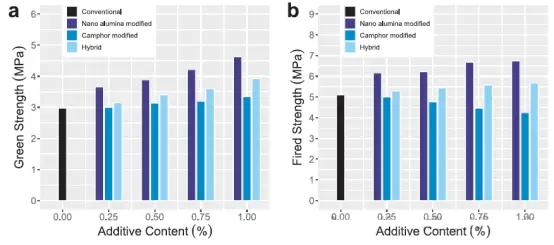

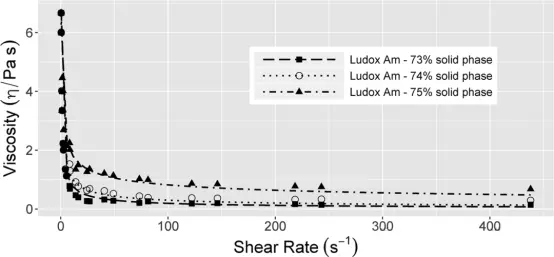

Through the above-mentioned fiber reinforcement mechanism, the bending strength was increased by up to 261% [46]. However, interestingly, the addition of fibers also improved the porosity of the structure. Despite the fibers not being completely burned off during firing, the porosity still exceeded 27%. This is attributed to the interwoven fiber network, which has been proven to induce a well-connected pore structure. This may be due to the improved pore distribution around the fiber network, which enhances the connectivity of the pores [46, 48, 49]. Another important component that affects the green and sintered properties of ceramic shell molds is the content of the binder. The main function of the binder is to provide sufficient green strength to the unsintered shell mold to enable the initial processing steps, but it also has a significant impact on various properties of the ceramic shell and core, including viscosity, stability, and post-sintering permeability. One of the commonly used binders in ceramic slurries is colloidal silica, which has replaced ethyl silicate binders due to government regulations [50, 34]. This is because colloidal silica can provide sufficient green strength and stabilize the slurry to prevent self-gelation and agglomeration [51, 52]. Multiple studies have found that various parameters of silica binders, including solid phase fraction and the ratio of filler to binder, have a significant impact on performance. As the silica content increases, the viscosity rises significantly (Figure 11), leading to an increase in bending strength and a decrease in permeability [52, 53]. This is because silica particles form a siloxane bond network during the drying process [54]. This process can be accelerated by adding electrolytes, which neutralize the silica particles and shorten the drying time [53]. Similar to the solid fraction, an increase in the ratio of filler to binder increases the density of the slurry, thereby increasing the viscosity and bending strength of the resulting shell [53]. In addition to traditional colloidal binders, a class of water-soluble binders that have received more attention in recent years also show potential for manufacturing ceramic shell molds with good mechanical properties. Among them, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), an organic polymer binder, is the most frequently studied water-soluble binder. Its viscosity (Figure 12) and bending strength increase with the increase in content [55, 56]. Another study also supports this view and further compares PVA with two polyacrylic acid binders in a silicon carbide ceramic system, with the mass fractions of the two polyacrylic acid binders being 20% (PA) and 40% (PA2) of ethylene-acrylic acid copolymer. The study found that at a binder content of 15% (mass fraction), the PA binder provided a more ideal combination of properties. These properties include relatively low viscosity and optimal bonding and stability [50]. More research is needed on the slurry system parameters of water-soluble binders to understand how to adjust these parameters to influence specific properties of ceramic shell molds.

3. Preparation Process

Investment casting is a classic metal processing method. Despite significant advancements in material technology, some aspects of it remain stable. The traditional "lost wax" casting process, which can be traced back thousands of years, is still very popular in modern times due to its low cost, high dimensional accuracy, and strong repeatability. Therefore, slurry impregnation technology is still usually the main method for making ceramic shells for investment casting. With the development of more complex systems and more precise casting specifications, including modern turbine blades, investment casting shells need to incorporate ceramic cores. These cores help form various internal geometries, mainly to increase cooling channels for temperature control [1]. Since its inception, the processing methods for these cores have also remained relatively stable, with injection molding being the main forming method. However, the extreme requirements of high-temperature alloy casting have exacerbated many limitations of traditional shells, especially the limited control over structural characteristics that may affect mechanical and thermal properties as well as the interface reaction between the melt and the ceramic shell.

3.1. Obstacles

Nickel-based superalloys contain multiple alloying elements such as titanium, cobalt, hafnium, carbon, tungsten, tantalum, rhenium, aluminum, yttrium, chromium, zirconium, molybdenum, and boron. These additives can influence physical changes by inhibiting and/or stabilizing different phases, thereby enhancing the thermal mechanical and chemical properties of the alloy [3–5]. For instance, hafnium at a concentration below 1% can improve the creep resistance of nickel alloys and slow down the initiation and propagation of microcracks during solidification [57]. Additionally, elements like chromium and aluminum can enhance corrosion resistance, while carbon and yttrium can strengthen grain boundaries to increase the mechanical strength of polycrystalline alloys [58,59]. However, although these elements and several others mentioned earlier are crucial for the alloy's functionality, they have also been shown to intensify the interface reactions with the ceramic shell during casting [21,60–62]. These layers, apart from other adverse effects, significantly increase processing costs and reduce the dimensional accuracy of the castings. Therefore, mitigating these chemical reactions during casting is a key step in forming more precise and cost-effective shells.

A widely adopted method to reduce interface reactions is to coat the outer surface of the core and the inner surface of the shell with inert coatings. These coatings are typically composed of metal oxides, nitrides, carbides, and/or silicides, which form non-reactive surfaces to reduce the diffusion of ions from the ceramic material into the alloy, thereby minimizing defects caused by chemical reactions.

Figure 11. The influence of the solid phase mass fraction of colloidal silica binder on the slurry viscosity, indicating that the viscosity increases with the increase of the solid phase silica content (reproduced with permission from Ref. [52])

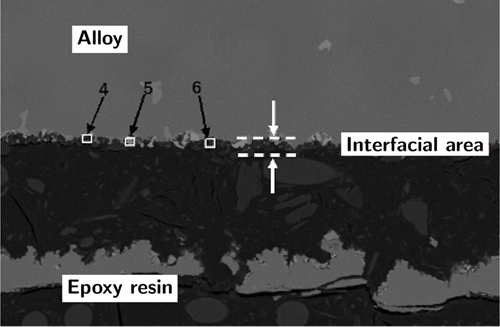

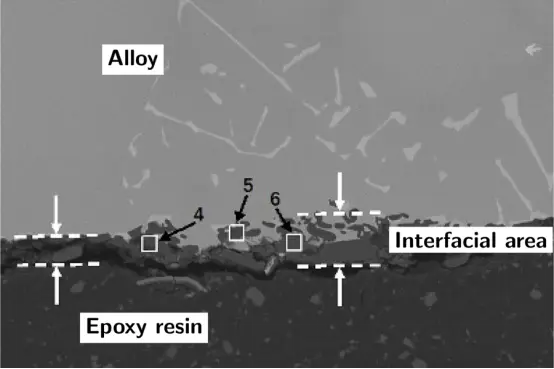

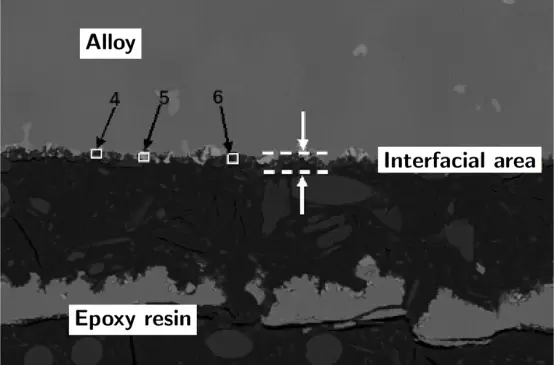

Figure 13. Interface area image of the molten alumina surface layer containing 5% (mass fraction) Cr2O3 (reproduced with permission from Ref. [60])

Figure 14. Interface area image of the molten alumina surface layer containing 5% (mass fraction) hexagonal boron nitride (reproduced with permission from Ref. [60])

This is supported by several studies that used modified alumina surface layers to mitigate the interfacial reaction. A preliminary study showed that adding 5 wt% of a ceramic powder composed of hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) and calcined kaolin to the surface layer could significantly reduce the alloy's wettability on the surface layer [63]. In a subsequent study, molten alumina surface layers with different h-BN additions were compared with alumina surface layers containing different Cr2O3 contents, and the reaction layer results are shown in Figures 13 and 14. The study indicated that the h-BN additive successfully increased the wetting angle, thereby reducing the melt penetration into the surface layer, while Cr2O3 did not have the potential to mitigate the interfacial reaction [60]. Another method of applying a barrier is to deposit a thin layer of aluminum on the surface of the shell to make it conductive. Then, the surface can be electrostatically powder coated, and the metal layer reacts with the alumina to become part of the reaction inhibition barrier coating [22].

3.2. Rapid Prototyping and Additive Manufacturing To overcome the common limitations of traditional shell-making techniques, including the difficulty in controlling thickness and the preference for certain chemical compositions, recent research has utilized rapid prototyping and additive manufacturing (AM) technologies to better control the structure of the shell. As discussed in the previous review, the edges of ceramic shells are potential sites for mechanical failure due to stress concentration and reduced shell thickness [33]. Traditional dipping techniques are unable to effectively address this issue, and to achieve sufficient strength to prevent crack propagation, other necessary properties such as permeability must be sacrificed [35]. With additive manufacturing, manufacturing flexibility is significantly enhanced, allowing for the creation of composite designs that can generate regions with varying chemical compositions, thicknesses, and mechanical and thermal properties at specific locations. By using stereolithography to form layered components, control can extend to the structural design level, not just simple dimensional adjustments. Stereolithography is an additive manufacturing technology that builds layer by layer through a photochemical process. In this case, each layer can be designed according to the required function of the component, thereby forming functionally graded components [64]. Compared to similar slurry-based techniques, this process has several potential advantages as it allows for the adjustment of the properties of each layer, resulting in more feasible shells. Studies have shown that additive manufacturing processes can be used to prepare outer core bodies composed of expensive and highly inert yttria-based powders, while the main body of the core uses lower-cost and more easily dissolvable ceramic materials. This enables the inertness of yttria-based ceramics to be utilized when in contact with high-temperature alloy melts, while mitigating the negative impacts of their limitations, as discussed in Section 4.4 regarding yttria. An intermediate layer is also introduced between the outer core body and the core body's main body to alleviate thermal stresses caused by differences in expansion coefficients and improve sintering performance [65]. Additive manufacturing can go even further, not only influencing the composition and structural control of the shell but also incorporating changes in geometry. For example, additive manufacturing can be used to incorporate pores and channels in the core body to enhance percolation in thicker and less permeable regions. The relationship between porosity and percolation has been well established in ceramic core processing and other applications [66, 67], and can be easily utilized through additive manufacturing. Another capability of additive manufacturing is the direct formation of wax patterns without the need for injection molding. Some researchers have noted the advantages of additive manufacturing in this application, as it reduces the considerable tool preparation time and costs associated with standard injection molding processes and wax pattern assembly [68, 69].

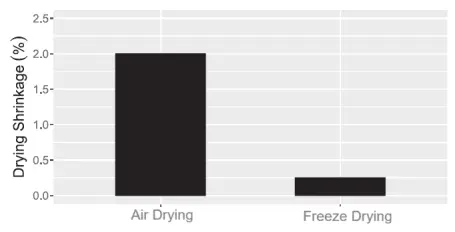

3.3. Gelcasting Method Gelcasting is a process often combined with additive manufacturing techniques for manufacturing ceramic cores. It is a near-net-shape process where ceramic powder is placed in an organic monomer solution and then poured into a mold. Gelcasting enables the mixture to polymerize into a high-strength, highly cross-linked gel, and it has a relatively short development cycle [70]. A gelcasting process for low-cost production of alumina-based ceramic cores was successfully developed by using a freeze-drying process to reduce shrinkage and inhibit crack formation, as shown in Figures 15 and 16 [71]. Further control of shrinkage can be achieved by adding less than 0.5% magnesium oxide powder, which offsets the natural sintering shrinkage of the core by forming an expansive MgAl2O4 [71,72]. Figure 15. (a) Cracks due to natural air drying and (b) inhibition of crack formation during the natural air drying process (reproduced with permission from Ref. [71]) Figure 16. Comparison of air drying shrinkage and freeze-drying shrinkage shows that freeze-drying results in significantly lower drying shrinkage (reproduced with permission from Ref. [71]) As mentioned earlier, gelcasting can be combined with complementary technologies to optimize various process parameters. In one study, additive manufacturing was combined with gelcasting to rapidly develop complex resin prototypes to replace standard metal molds. These models have the advantages of lower cost, shorter lead time, high forming accuracy, good rigidity, and excellent surface quality [71]. Similarly, a ceramic core for casting aluminum, magnesium, and titanium alloys was developed through gelcasting. This method used a calcium-based slurry and water-soluble epoxy resin, with a green density of the green body of 58.5% and a bending strength as high as 29.5 MPa. Additionally, the water solubility of the core facilitates the removal of the core after casting, overcoming the limitation of leachability [73]. Despite these encouraging characteristics, the relatively high sintering shrinkage rate of over 11% indicates a significant risk of cracking, which is a common problem in many gelcasting processes. Moreover, there is no evidence that this process can be applied to nickel-based superalloys. Another key processing consideration, as mentioned multiple times earlier, is the permeability of the ceramic shell, which allows gases to escape through the shell. To improve the permeability of sintered ceramic shells, many processes use pore-forming agents (PFAs) in the ceramic slurry, which burn off during firing, leaving pores and thus enhancing the shell's permeability. Due to the difficulties often encountered when transitioning to fibrous pore-forming agents, recent studies have returned to an approximate method of traditional pore-forming techniques, namely the needle coke sintering process, in which needle coke is used as a filler in the ceramic slurry. Needle coke is particularly popular because of its high strength, low expansion coefficient, good thermal shock resistance, and low cost [74]. Compared to traditional fused silica shells, the addition of needle coke increases the overall shell thickness by 30% and the edge thickness by 60%, without the need for additional coatings, thereby reducing permeability and production time. Moreover, shells with petroleum-induced pores exhibit greater green strength and comparable thermal strength compared to the fused silica system, indicating that strength can be maintained even with increased porosity, as shown in Figures 17 to 19 [74,75].

4. Ceramic Materials

As mentioned earlier, the ceramic materials used for investment casting shells have a significant impact on the feasibility of the casting system and process. The primary considerations include reactivity, leachability, mechanical properties, thermomechanical properties, and processability. Ceramic oxides have proven to be the most successful ceramic materials for casting superalloys because they are less reactive with the melt. The main ceramic materials used in ceramic shell design - and those to be discussed in this review - are silica, alumina, zircon, and yttrium-based materials. The historical performance of these ceramic materials in the above-mentioned key properties will be examined below.

4.1. Silicon Dioxide

Silicon-based materials made from fused silica (SiO2) are among the most popular ceramic materials for casting high-temperature alloy components. As a polymorph, the properties of silicon dioxide vary significantly depending on its phase. The main phases of silicon dioxide to be discussed here are fused silica (its amorphous form) and cristobalite (the mineral polymorph at high temperatures). In its amorphous state, it has many advantages in high-temperature environments, including an extremely low coefficient of thermal expansion (0.6×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹), which gives it excellent thermal shock resistance. Fused silica also has good leachability and can be removed using aqueous solutions of sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide without damaging the casting alloy itself [24]. However, the most influential feature of fused silica lies in the controllability of its mechanical and thermal properties. Standard fused silica softens, making it prone to deformation under stress during sintering, including creep. This issue can be addressed by enhancing the strength of the shell, which largely depends on two factors: apparent porosity and the transformation of cristobalite [24]. Cristobalite is a mineral polymorph of silicon dioxide that forms on the surface of fused silica particles during sintering at high temperatures [76]. This transformation dominates the sintering behavior of fused silica-based ceramic materials at high temperatures, such as in casting applications, where it can enhance the strength of the core. The initial transformation to the β-cristobalite phase has been shown to increase the strength and volume density of fused silica shells, as illustrated in Figure 20. The bending strength of the sample sintered at 1300°C (11.4 MPa) is higher than that of the sample sintered at 1200°C.